| Type | Book |

|---|---|

| Date | 1938 |

| Tags | China, picture book, children's book, fiction |

Mei Li

Mei Li wishes to go to the New Year Fair in the city, but little girls always have to stay home. Undaunted, she sneaks out to visit the city, following her brother. What adventures await?

Thomas Handforth's Mei Li is the winner of the 1939 Caldecott Medal. Unlike the previous winner, Animals of the Bible: A Picture Book, Mei Li is a real picture book.

The story centers around a young Chinese girl, Mei Li, who is unsatisfied with remaining at home, while the New Year Fair is going on. "If I always stay at home," she asks, "what can I be good for?" So off she goes to have adventures like her brother, San Yu. He wonders what a girl could do at the fair, but she bribes him to take her with him, all the same.

The fair is as exciting as Mei Li had hoped, and she shows her doubting brother all the things that a girl can do, at the fair. Looking at a group of circus performers, she tells him, "They can walk on stilts. They can balance on a tight-rope. They can throw pots and pans in the air with their feet. And so can I!"

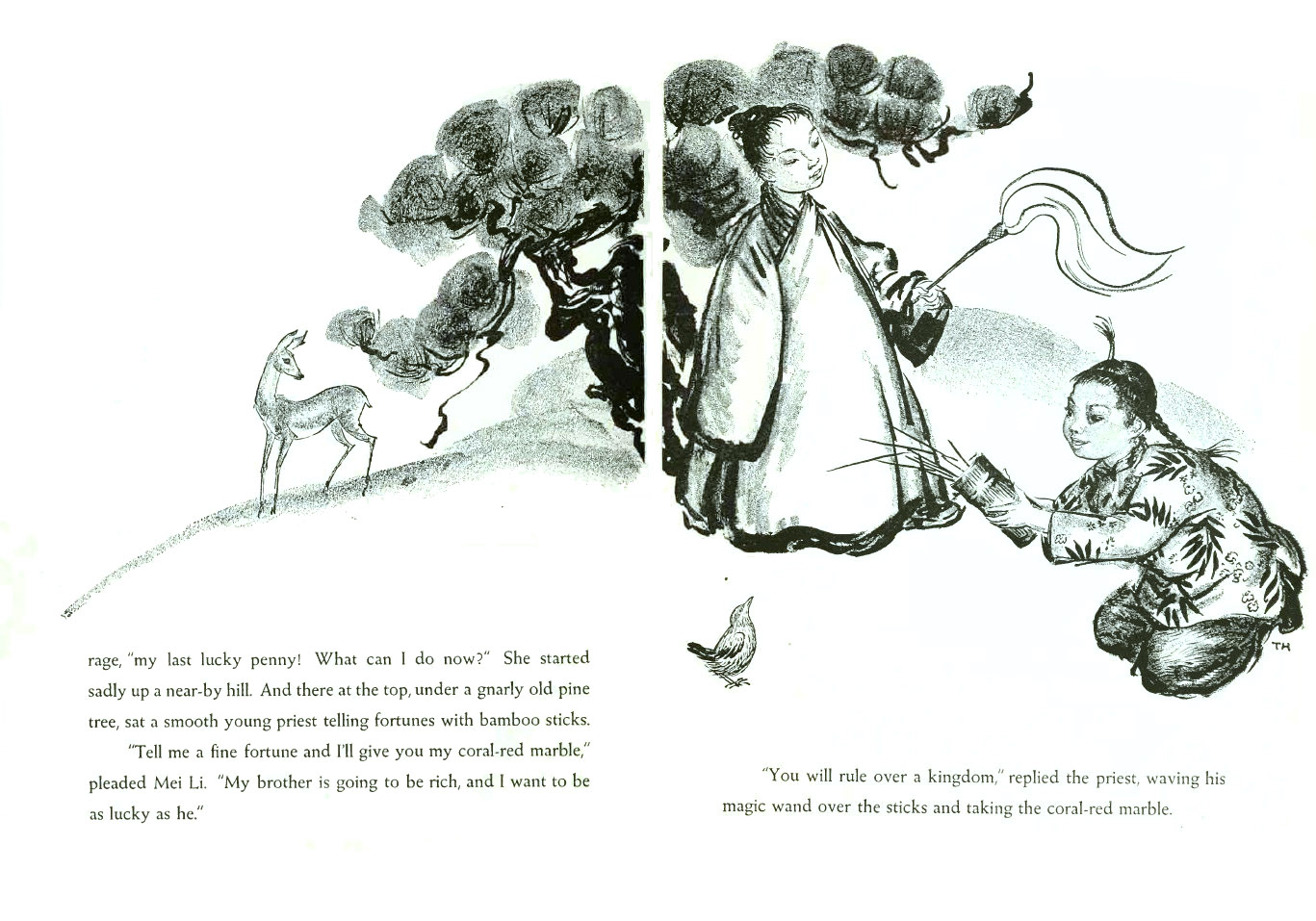

Mei Li doesn't juggle pots and pans with her feet, but she does ask a strong circus girl to lift her upside-down in the palm of her hand; she feeds a bear a bit of bean-cake; and she dances on the back of a circus pony. Later, a fortune teller predicts that Mei Li will rule over a kingdom--naturally, she believes him. Soon after, they must hurry home, so they will be in time to greet the Kitchen God.

When she returns home, Mei Li's mother refers to her as "the princess who rules our hearts." She is surely a princess, but what sort of kingdom will she rule over? That night, the Kitchen God explains:

"This house is your kingdom and palace. Within its walls all living things are your loyal, loving subjects."

Mei Li sighed happily, "It will do for a while, anyway."

Mei Li is based on Handforth's experiences while living in China for six years, beginning in 1931, the characters and drawings are based on people he knew, and the titular heroine is based on Pu Mei Li, a four-year-old girl he met there. Much more information about this, including a photograph of the real Mei Li holding Handforth's picture book, can be found in this article from The Horn Book Magazine by Kathleen Horning (who, coincidentally, wrote From Cover to Cover: Evaluating and Reviewing Children's Books, which I read almost exactly two years ago).

The illustrations are in ink, done with a brush, which Handforth felt better captured the spirit of China. Few of the illustrations feature any background, but the figures represented are generally very dynamic. The book does feature a number of two-page spreads, varying text positioning depending on the artwork. The illustrations depict the actual scenes in the book, making Mei Li much more of a 'real' picture book than its predecessor for the Caldecott Medal.

Mei Li has been criticized for sexism. Not without grounds: Mei Li is told that her 'kingdom' is the home, and the book ends with a poem extolling the virtues of a woman who keeps a good house:

This is the thrifty princess,

Whose house is always clean,

No dirt within her kingdom

Is ever to be seen.

Her food is fit

For a king to eat,

Her hair and clothes

Are always neat.

Furthermore, Mei Li is shown to be frightened of fireworks, allowing San Yu to set them off while she plugs her ears, and she gives her last lucky penny to San Yu to throw at a bell (for the promise of money all year), since she is sure that she could never hit it.

I think these criticisms are a little misguided; at least, they don't look at the whole picture. Compare what Mei Li does at the fair to what San Yu does: while Mei Li balances upside down on a circus performer's hand, San Yu dresses up as a wise man for a play; while Mei Li feeds a real bear a cake, to show her bravery, San Yu pretends to hunt a lion that is really two boys with a mask; Mei Li dances on the back of a prancing horse, after which San Yu throws her penny at a bell and goes off to buy a kite (a fake hawk, which he later uses to frighten Mei Li). Mei Li's adventures at the fair are real, and San Yu's are merely imaginary. Certainly it is Mei Li who comes off best in their little competition!

Too, Mei Li gives her first lucky penny to a beggar girl she meets when entering the city, and it's that girl who holds the gates open so that she can leave the city and return home to greet the Kitchen God, "And even five policemen and five soldiers could not force her away until Mei Li was through the gate." Not so easily cowed, this girl!

Finally, though the statement of the Kitchen God that the house is Mei Li's kingdom may be reinforcing the domestic role of women, Mei Li responds that it will do "for a while, anyway", which also means that eventually, it won't be enough. And Handforth wrote, of the real Mei Li:

No Empress Dowager was ever more determined than she. A career is surely ordained for her, other than being the heroine of a children’s book.

Certainly some older children's books do not stand the test of time, as cultural values march on (The Five Chinese Brothers or Shen of the Sea, both coincidentally also dealing with China, are examples of this, for different reasons), but I wouldn't fear to recommend Mei Li.

Relatively little is to be found online about this book or its author. There is some other material from The Horn Book Magazine, linked above, including the magazine's contemporary review of the book, written by Elizabeth Coatsworth, originally published in the July-August 1939 issue. The Art Institute of Chicago, The Smithsonian American Art Museum, and The Seattle Public Library Northwest Art Collection each provide a few samples of Handforth's other art, including one picture which must (I think) have been the original model for a scene from Mei Li.

Altogether, I find Mei Li to be a much worthier recipient of the Caldecott Medal than its predecessor, and a good book, besides. I hope that the later recipients continue more in this vein!

| Name | Role |

|---|---|

| Thomas Handforth | Author / Illustrator |