| Type | JournalArticle |

|---|---|

| Date | 2015-02-10 |

| Tags | nonfiction, games, complexity |

| Journal | arXiv |

Classic Nintendo Games are (Computationally) Hard

I came across an interesting paper on arXiv, "Classic Nintendo Games are (NP-)Hard" by Greg Aloupis, Erik D. Demaine, Alan Guo, and Giovanni Viglietta. The paper is originally from 2012, but it's been updated in February of 2015 with additional results. It's been mentioned a few times on the web, but I didn't see anyone give a satisfactory explanation of what the paper is really about. I'm not an expert, but I'll give it a go.

What does it all mean?

I'll go into some detail shortly, but I'd like to describe in broad strokes what this is (and isn't).

The authors look at how hard it is to answer the question: given a particular level layout, a starting point, and a finish point, is it possible to get from the start to the finish?

This isn't about the levels actually in the games--in fact, it isn't really about the level design at all. What it is about is the rules of the games. Super Mario Bros., for example, has several well-known rules:

- Mushrooms make small Mario big.

- Touching enemies (or some other hazards) makes big Mario small, or kills small Mario.

- Mario can break bricks only if he's big.

- Stars make Mario temporarily invulnerable.

- Mario can jump to a height of 4 tiles, or 5 when running.

There are more rules, but you see the point. Importantly, the authors specify that their results are about an idealized version of the rules. In other words, glitches don't count. Sorry.

What the authors prove is that if you turn someone loose with a level editor, they can design a level for which it is very hard to determine whether it's even possible to complete.

They do this by showing that you can implement a problem called the 3-satisfiability problem (or 3-SAT) in each of the games. Think of someone using redstone to make Tetris in Minecraft, and you've got the general idea. 3-SAT is known to be NP-complete (read as: difficult), and the game it's implemented in must be at least as hard as 3-SAT. Those problems are called NP-hard.

Details

The 3-satisfiability problem is to determine if, given a boolean formula of a certain form, it is possible to set the variables (which can be either true or false) in such a way that the whole formula comes out true. A two-variable example of 3-SAT might be:

(y is TRUE | x is TRUE | x is TRUE)

AND

(x is FALSE | y is TRUE | y is TRUE)

AND

(x is FALSE | y is FALSE | y is FALSE)

(Don't be alarmed by the duplication. The reason for writing that way will be apparent later.)

The 3 in 3-SAT means that each clause (the parts in parentheses) can have at most 3 components. In this case, each has only two distinct components--one is repeated.

All three clauses must be true for the formula to be true, and a clause is true if any of its components (which are separated by pipes) is true. In logic-speak, it's a conjunction of several disjunctions.

It's pretty easy to see that this expression is true if y is true (satisfying the first part) and x is false (satisfying the other two). But what if there were fifty or a hundred or a billion sub-expressions? That would be harder to tell.

Requirements for 3-SAT

To be able to implement 3-SAT, you need a few components. You need:

- A starting point

- A finishing point

- A way to pick whether a variable is true or false

- A way for those choices to either impede or allow progress

- A way to let paths cross without being able to change from one path to another

That last one is so that you can build big, complex paths. Without it, you'd be able to backtrack and mess things up.

The authors implement these components in 'gadgets', which are basically self-contained rooms or screens that can be connected to each other. They're the building blocks of the satisfiability puzzle.

Gadgets in Super Mario Bros.

I'll take a brief look at how the authors build these gadgets for Super Mario Bros., as an example. This is going to be pretty much the same as what the authors say in the paper, so if you're feeling industrious, you can look at the paper and see how they put it.

Start

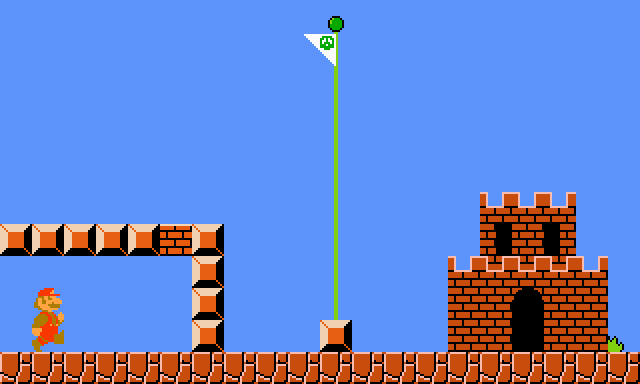

The start gadget is just where Mario starts the level--there's nothing to it. In general, the authors want Mario to be big throughout the level, so they put a mushroom at the beginning that will be required at the finish.

Finish

Again, this is trivial. It's just the flagpole. To make sure Mario stayed big throughout the level, you have him enter the screen with the flagpole in a corridor with a brick he must break to reach the flagpole.

Variable

To pick whether a variable is true or false, Mario is given a screen with two possible paths--a vertical drop to either the left or right. Say left means "x is true" and right means "x is false". It doesn't matter which. The drops are long enough that Mario can't get back up, so once a choice is made, Mario can't go back and also take the other path.

Clause and Check

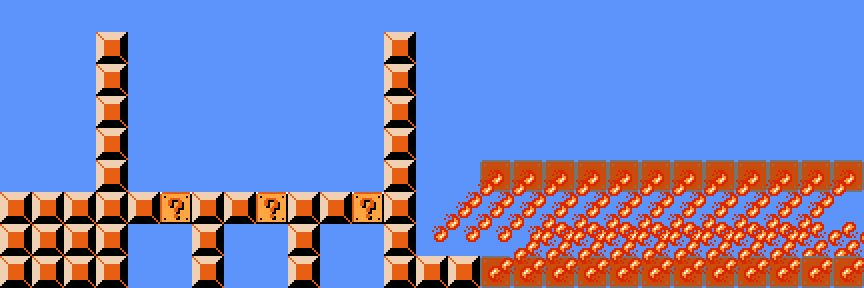

This is the most interesting (and important) gadget in Super Mario Bros. Take a look at it:

After making a choice and dropping from the Variable gadget, Mario will be led to a series of Clause gadgets. He enters one of the small open areas from the bottom--each one of them will have a path from a Variable gadget that leads to it.

Each block contains a star, which will be trapped in the 'fence' when Mario hits the block. Later, Mario will come through the top part (that's the Check part of the gadget) and collect the star so that he can run through the Firebars. If Mario gets to the Check gadget without having hit the star block (thus satisfying the disjunction), he can't proceed--the Firebars will kill him.

Remember our example of 3-SAT from earlier?

(y is TRUE | x is TRUE | x is TRUE)

AND

(x is FALSE | y is TRUE | y is TRUE)

AND

(x is FALSE | y is FALSE | y is FALSE)

Imagine that the gadget pictured corresponds to the top disjunction, (y is TRUE | x is TRUE | x is TRUE). Then Mario will reach the left star block if he picked "y is TRUE" by dropping down the left side of the corresponding Variable gadget, and the middle and right star blocks by picking "x is TRUE" by dropping down the left side of that particular Variable gadget.

But what if Mario picked "x is false" and "y is false"? Then he'd never get to the blocks and release the star, so when he got to the Check gadget, the Firebars would kill him. That means that both variables being false isn't a solution to the expression, and (equivalently) taking the right path at both variable gadgets won't let Mario finish the level.

Crossover

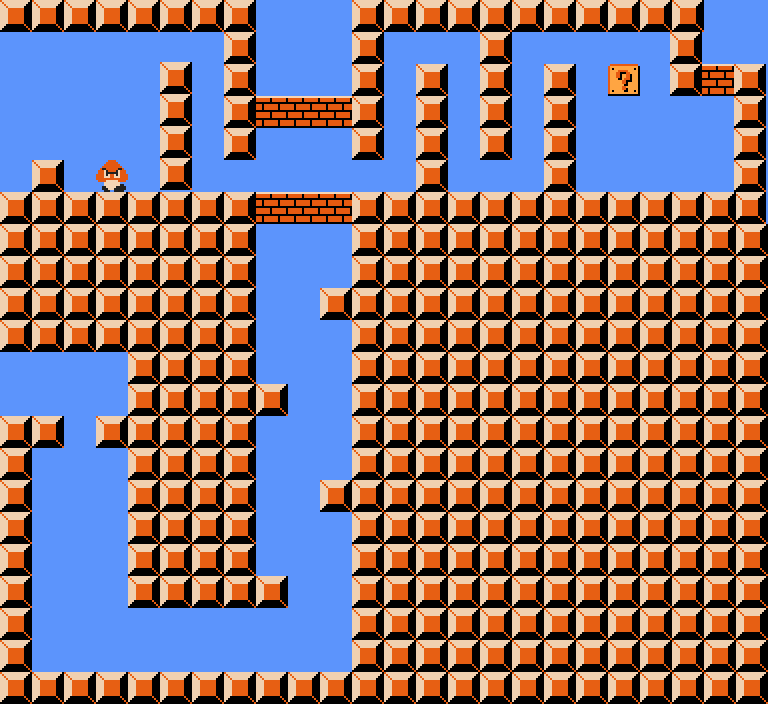

This is just a utility to let paths cross without Mario backtracking and making two different choices for one Variable.

If Mario comes in from the lower path, he can break the bricks and keep going up.

If he comes in from the upper path, he can run into the Goomba to become small, head to the right, pick up the mushroom from the block, break the brick, and continue to the right.

Small Mario can't break the bricks in the middle to go up, and big Mario can't get through the narrow paths to go to the right. Big Mario also can't break the bricks and then go back, because the drop on the left is too far for him to get back up.

Putting it all together

You can string together as many Variable, Clause, and Check gadgets as you need to make as big of a problem as you want. Since we know that 3-SAT is NP-complete, and we've just implemented 3-SAT in Super Mario Bros., we know that SMB is NP-hard.

Congratulations! If you've made it this far, then you've got the major idea of (part of) the paper. Pick up your CS degree on the way out the door.

Other games, other problems

I won't go into detail about the other sections of the paper, but if you've read this far, you should be able to read the paper and see what is being done. The proofs for other Mario games just make some modifications to the gadgets we looked at above.

The proofs for the Zelda games are different. They still work by implementing an NP-hard problem, but it's a different problem, and they implement it using the sliding blocks in the Zelda series.

If you want to know about the other games, or get more details, take look at the paper.

Caveat lector

I've done my best, here, but I'm not an expert. I've got a BS in math, not a doctorate in computer science. If I've made some terrible mistake, it's all my fault (and I'd appreciate it if you'd let me know!), and I apologize for anything misleading, confusing, or dangerous that I've written. Always wear proper safety equipment when proving theorems.

Abstract

We prove NP-hardness results for five of Nintendo's largest video game franchises: Mario, Donkey Kong, Legend of Zelda, Metroid, and Pokemon. Our results apply to generalized versions of Super Mario Bros. 1-3, The Lost Levels, and Super Mario World; Donkey Kong Country 1-3; all Legend of Zelda games; all Metroid games; and all Pokemon role-playing games. In addition, we prove PSPACE-completeness of the Donkey Kong Country games and several Legend of Zelda games.

| Name | Role |

|---|---|

| Alan Guo | Author |

| Erik D. Demaine | Author |

| Giovanni Viglietta | Author |

| Greg Aloupis | Author |